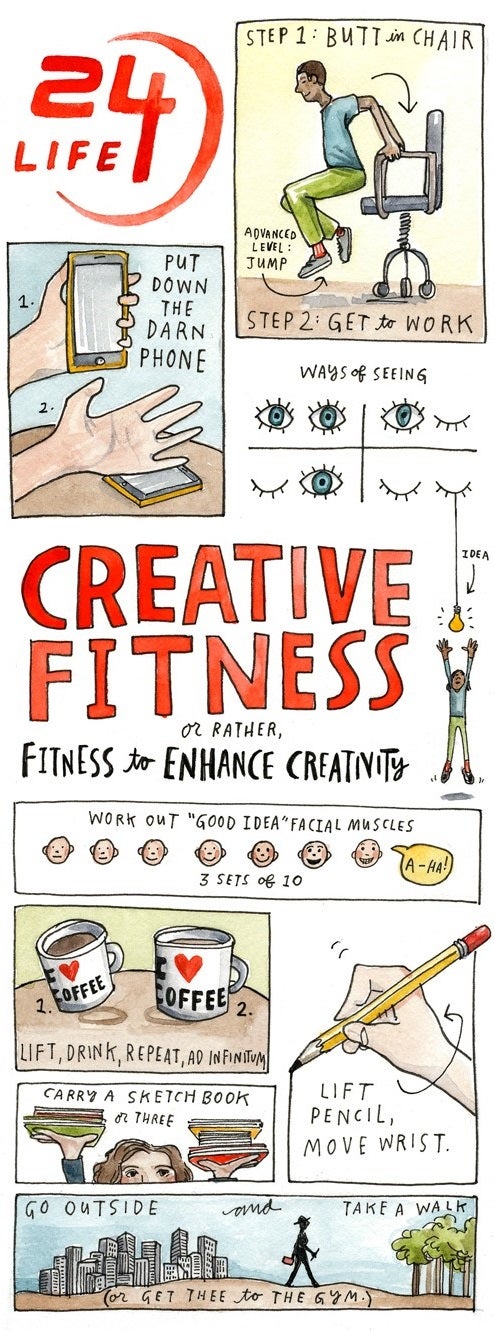

Wendy MacNaughton: We’re Born Creative

The popular illustrator finds creativity in collaboration-on city streets, around the conference table and in the kitchen.

Wendy MacNaughton earned her degree in fine arts. But she began to make a living drawing and painting only in the last six years, and almost by accident-when she started drawing her fellow commuters and posting her observations and drawings online. She firmly believes everyone is born creative, that art lies in collaboration (whether between story and visual storyteller or among coworkers), and that inspiration lies in the humblest observations.

Her work is everywhere, it seems, from her back page column in California Sunday magazine to The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time magazine, Bon Appetit and NPR. Her books include “Meanwhile in San Francisco: The City in its Own Words” (Chronicle Books, 2014), “Lost Cat: A True Story of Love, Desperation, and GPS Technology” (Bloomsbury, 2013), “The Gutsy Girl” (Bloomsbury, 2016) “Knives & Ink: Chefs and The Stories Behind Their Tattoos” (Bloomsbury, 2016), and most recently, celebrated chef Samin Nosrat’s highly acclaimed “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat” (Simon & Schuster, 2017). This latest book is an illustrated guide to the elements that, once mastered, are the foundation of all good cooking.

24Life visited MacNaughton late one afternoon at her studio in a decommissioned wartime-shipbuilding office with sweeping views of the San Francisco Bay and the glow of the setting sun reflecting off the East Bay hills. She is a self-described illustrator and graphic journalist, so the conversation about creativity begins with MacNaughton’s precise explanation of what she does: “I think of illustration as finding stories in the real world and then bringing them to life through visuals.”

She then explains that a graphic journalist tells true stories with pictures: “I will go out, and I’ll spend a lot of time with people, sometimes up to a month. I’ll write down everything they say. I’ll draw from life, and then I’ll take the drawings and words and put them together to tell a true story.”

Creativity is something we’re born with

MacNaughton rejects the notion that some people are creative and some are not and also refutes what she calls “the myth of the lone artist.” MacNaughton acknowledges, “You might get an idea alone in a room, … but that’s through a chain of events that inevitably involved interactions with other people. So I think collaboration is this missing element when people talk about creativity.”

What’s more, from her perspective, creative people are simply distinguished by their powers of observation-something that all of us can develop. “Creative people are like collectors of things. They’re looking at things. They’re paying attention to things. They are arranging the things they find in unique ways, making new combinations of existing things.” MacNaughton’s series of drawings called “The Commuters” came to life from observing and sketching her daily ride on BART to her job as a copywriter in San Francisco.

Now, she sketches (and paints) a weekly series called “Meanwhile,” an extension of her book “Meanwhile in San Francisco,” which collected her stories and sketches from conversations with people representing all walks of San Francisco life and subcultures, from a tough stretch of 6th Street to dog walkers and the hip café crowd. MacNaughton says, “When you combine unlikely things together in an open-minded way, that’s when you have a creative epiphany.”

Art results from experience and collaboration

As for her relatively late start on her artistic path, MacNaughton is pleased with the timing. “My mom used to say this thing that I thought was really cheesy [as a kid]: ‘In life you have a basket, and you walk along with your basket, and you have all these experiences, and you put your experiences in the basket, and then eventually, you get to the place you’re going and you have all these riches that you didn’t expect, and that is what you have to work with in your life.’“

MacNaughton now understands what her mother meant: “When I started drawing again, I had a clear sense of who I was, … what I wanted to do with my work and my time, and what I wanted to say.”

Crucial among those experiences are her encounters with people from all walks of life. Through her sketchbook and pen, MacNaughton finds a way to engage people in telling their stories and collaborating on art. She explains, “My work can be collaborative, like if I [do] illustrations that go with an author’s words for a book or for an article. But I also consider all the people that I speak with in the stories that I do [to be my] collaborators.”

MacNaughton is quick to give credit for that collaboration. “People are sharing their lives and their stories with me. … So even though my name might be attached to that story, I always try to give thanks to the people who have shared their stories, [because] we’ve collaborated to take it out to the world.”

Creative collaboration drives change

With collaboration as her philosophy and approach, MacNaughton sees a parallel between making good art and doing good for the world. “The lone artist is this myth that this country also is kind of built on, that there’s this one person who’s the hero. … That’s not the way sustainable change-or sustainable anything-ever happens. It’s when a group of people work together for the benefit of all. … [Good] community work is done that way, and I also think good artwork can be done that way, too.”

To put a finer point on it, MacNaughton says, “One person might be looking at a painting in a room alone, but that person is seeing it through all of the conversations [she’s] had through reading, through looking, through conversations with the people who have come before and the people who are working in the world right now. … It just makes for better work and makes for a better world.”

That’s where everyone’s capacity for creativity comes into play. MacNaughton says, “You don’t have to draw. You don’t have to paint. You don’t have to be able to make music. Creativity is like a spirit of generativity. … If you see something, and you’re not happy with the way it is, well, let’s figure out new ways to address that. Come at it from the side. Come at it from a different angle. … You can apply that to any field.”

The moment for visual creation

MacNaughton does think it’s a great time to be an artist, though, because there are so many different ways to connect. “Most of us are creating something … to connect with people,” she says, and she notes that social media affords the means to do so: “Facebook and Instagram and blogs and even LinkedIn, for that matter, are all platforms you can choose to put our work out there, … to get a conversation going between people who look at your work and you, who’s making it.”

MacNaughton has a special message for people who are “image creators in any sense of the word: an illustrator, an artist, an art director, a graphic designer, anybody who’s working with visuals in some way.” In a world where everything is visually driven, from TV and movies to social media, she says these individuals are in “a really, really powerful position right now, [and] they have a wonderful opportunity to use that for a positive impact.”

MacNaughton explains one reason she draws from life is to capture something in the moment that drawing from a photograph or from memory cannot. She speculates that’s what triggered the overwhelming response. “A ton of people wanted that image, and I ended up making prints and raising a ton of money for organizations that support women’s rights using that image. And now it’s out there in hundreds of people’s homes as a reminder of a positive future and solidarity and the good that we can accomplish together.”

“SALT, FAT, ACID, HEAT”

MacNaughton’s most recent project is “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat” by Samin Nosrat. MacNaughton says Nosrat is “teaching everybody how to cook and how to approach food in a way where you don’t really need a recipe.” MacNaughton spent five years observing Nosrat, “drawing over her shoulder” and creating “a ton of charts and diagrams and all this stuff that helps you understand a ton of information … in a really accessible, fun way.”

MacNaughton confesses that when Nosrat first visited the illustrator’s home, the chef opened the kitchen cupboards and found nothing but protein bars. MacNaughton also was Nosrat’s principle subject. “She taught me how to cook. And I asked her a million questions. … Those helped her clarify how to convey stuff to a newbie like me.”

Of course, standing over Nosrat and drawing meant a huge meal left at the end of a day’s work. So, MacNaughton says, friends were invited, and there were incredible meals for five years. She laughs and adds, “I put on a little bit of ‘love.’ Let’s put it that way.” She and her partner decided to see a nutritionist, and MacNaughton laughs again, recalling the advice they received: To put on muscle, her partner would need to eat more, and to lose fat, MacNaughton needed to eat less. MacNaughton also hit the gym: “By the third week, I felt a little bit stronger [from lifting weights and cardio]. Already some change happened just in how I was feeling. And now, I seriously feel great.”

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

Here are Wendy MacNaughton’s tools and tips for creativity-and her snack of choice when she’s in the middle of a project.

1. Pen of choice: Micron 02 pen

2. Power food: Croutons

3. Act when the muse strikes: “If she shows up while you’re shopping at Target, get outside or pull out a piece of paper or do whatever you have to do to write it down, to do the drawing, to write down the lyrics or the notes or whatever it is. I think it was Elizabeth Gilbert that said f you don’t the idea in that moment right then, it will pass through you and move onto someone else more ready to grab it. I completely agree.

4. Conquer artist’s block: “Every single time I start any project, I am terrified. … I think that this is just going to be the ultimate exposure that it was all dumb luck and I actually can’t do this. [So] I just draw whatever I see in front of me. I write down whatever I hear. I go to a coffee shop. I sit there and have a cup of coffee, and I draw the cup of coffee 12 times. Just get my hand moving. Get my brain moving. … And then the ideas start to come.”

5. Practice imperfect: “It’s about the love of doing it, so just keep doing it every day. Honestly, what it’s really about is going to the table every single day and sitting down with a piece of paper or going to the gym, and doing that thing every single day. It’s a practice, and who you are at the end of that six months is not the same person you were when you started.”

6. Find the funny: “When somebody goes into a gallery and they don’t get it, they don’t have to get it. … If it strikes you emotionally, that’s awesome. If it doesn’t, then walk out. … If it’s not for your world, don’t even worry. … I want [art to make me] laugh. Life can be funny and ridiculous and dumb. Let’s see more of that.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCuRt_35ijY

Drawings: Wendy MacNaughton

Photo credits: Mark Kuroda, KurodaStudios.com; (book jacket) Simon and Schuster; (croutons) 5PH, Thinkstock