San Francisco Shock: A New Kind of Athlete

“Esports is gaming,” Brett Lautenbach tells anyone who’s unfamiliar with the subject. Lautenbach is president of NRG, a company that fields teams in game-specific leagues.

Organized, competitive video gaming has been around online since the late ’90s, but in case you blinked, it has grown into a billion-dollar industry. Think NFL and NBA teams with their own esports entries and entertainment and sports giants such as Jennifer Lopez and Shaquille O’Neal as investors. The category has the equivalent of its own broadcast network: the Twitch streaming platform. And industry analysts at Newzoo predicted last year that 380 million people around the world would watch esports and that nearly half of those could be categorized as frequent viewers.

Now, imagine those millions are not only watching your every move, but they’re also listening to every command and split-second strategic decision between you and your teammates. They’re your peers, with a median age of 25, according to research firm Nielsen’s esports insights.

You’re beginning to get the picture: Esports athletes are not just kids playing in their bedrooms or basements. With the stakes for these players arguably as high as professional (conventional) athletes, NRG had the foresight to partner with 24 Hour Fitness in support of players’ health. 24Life asked Lautenbach and two of NRG’s star players on San Francisco Shock, a team in the Overwatch League, for more insight into a new kind of competition and what it takes to be a new kind of athlete.

Meet the players

Jay “Sinatraa” Won just turned 19 and takes his in-game name from Logic, a favorite rapper who has recorded with the moniker “Young Sinatra.” Sinatraa began playing games as a young teen and joined Counter-Strike teams. He estimates that by 15 or 16, he was playing in tournaments. When he actually won money for the team’s third-place victory and made his mom proud, he decided to pursue esports as a career.

Matthew “Super” DeLisi is 18 and has had computer games on his mind since he was little more than a toddler. His big brother indulged him with an account using the handle “Super” with “a bunch of numbers after it,” he says. Eventually, he dropped the numbers but the name stuck.

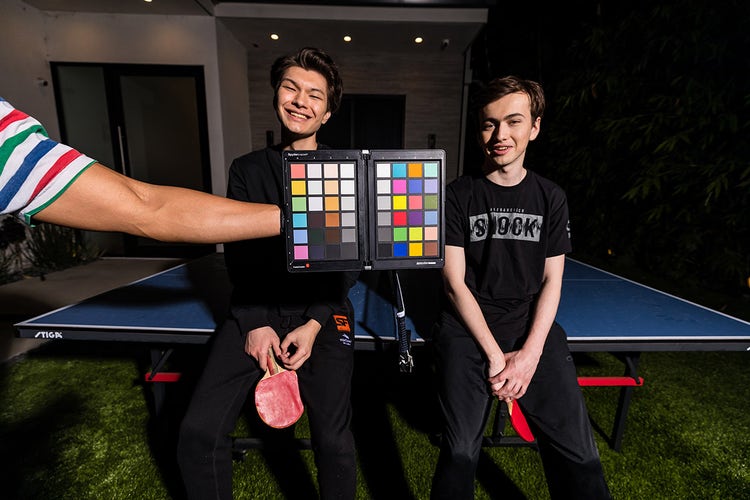

Sitting down with Sinatraa and Super in the team’s house in Sherman Oaks, California, their camaraderie is clear. They could finish one another’s sentences if they wanted to but just as easily take turns answering questions. And when huge paychecks and egos dominate conventional sports headlines, it’s refreshing to hear Lautenbach explain that team ethos is an explicit part of the conversation when NRG and prospective players are in recruiting discussions.

“This team in particular—they’re just brothers in arms to the end,” Lautenbach says. “They don’t go anywhere without at least one other person on the roster,” whether that’s for boba tea or a movie.

Team culture is one reason NRG decided to establish a team house—Lautenbach says management polled the players and they wanted a communal space. It’s an airy, open layout with two practice rooms that have stations around the perimeter so that players and coaches can crisscross the room during play, a media room with a giant screen and sofas, and a sunny patio whose main feature is a heavily used pingpong table.

The weapon with the biggest impact

To be sure, the objective of Overwatch is destruction. The roles in the game include “DPS,” or damage per second, and that’s Sinatraa’s primary role. The “tank” role—that’s what Super plays—creates space for the DPS role to do its job and also to absorb damage from the opposing team. “It allows your teammates to get better position, and be more aggressive, and be able to do the things that they need to do,” Super says. (There is a healing role, as well.)

Overwatch game roles have special powers and abilities that in some cases are designed to be complementary. (One character’s actions enhance or boost the impact of another’s.) But the biggest impact comes from something other than big weapons.

“Overwatch, especially, is a game [that’s] about communication and teamwork,” Sinatraa explains. “You can be the six best players in the world, but [if you] have bad teamwork or bad communication, you’ll be a really bad team.” The converse, he says, is also true: “You can have six OK players who are really good at working as a team, and they will be the best team in the world.”

Super adds that getting along well does more than lighten the mood. “It also helps when you come to criticizing or feedback; if you like someone, then you’ll be more open to accepting their feedback,” he says.

What’s more, the team’s communication skills are put to the test across languages. San Francisco Shock has six players from Korea, five American players and one player from Sweden. The minimum age required for league play is 18, and for these players, it’s an immersion experience equivalent to study abroad, Lautenbach explains.

Sinatraa expresses immense respect for his teammates’ efforts to learn English on the fly. “When it comes to communicating, we try to help simplify things so that it’s easier for them to understand,” he says. Still, when complex strategies or maneuvers can demand that, the more advanced English speakers translate “midgame, really fast.”

Teamwork under very bright lights

Sinatraa and Super are surprisingly comfortable with the very public nature of competition. Games are played nearby, at The Burbank Studio, where a sound stage has been built, stadium style, with the audience surrounding the stage. Super describes coming out of the tunnel onto the stage, seeing people high-fiving—and his nerves quickly giving way to the game. “When I sat down and just got focused, I thought, OK, it’s a cool thing that I’m here, but I was just ready to play,” he says.

Sinatraa admits to a reaction when he walked onstage at the esports World Cup tournament at the Anaheim Convention Center in Anaheim, California and realized how many people were watching the playoff competition. “It’s literally a 360-degree stadium, and it’s packed, and there’s the top play highlights on ESPN,” he says. (He placed among those top plays.) “I got goose bumps. That’s not even a joke.”

Yet the public eye does not close on esports athletes as it might for traditional athletes. Where conventional sports figures may remain beyond fans’ reach, esports competitors are active on social media and accessible to their fans to an extreme that Super agrees is different. Sinatraa makes a point of streaming—spending time interacting with fans—and acknowledges there are some “who message you … a lot.”

But from both players’ descriptions, the esports fan base appears to be one that’s more interested in the athletes as individuals rather than critical—as in the case of conventional athletes—of their failure to meet perfection.

Grinding hard

As glamorous and thrilling as competition sounds, the work that players put in sounds grueling. “The mental energy is crazy,” Sinatraa says. “We’re literally practicing eight, 10 hours a day. And then after that, we’re practicing on our own just to try to be the best individual player we can be.”

Super emphasizes how demanding constant communication can be. “You have to talk so much about enemy positioning, your positioning and then things you have to do in the fight,” he explains. “After a day of practicing and screaming, it’s really mentally draining for sure.”

With 17 maps for gameplay, 30 character roles from which any team of six might choose and periodic patch releases (updates to the game) from the game developer, the potential challenges seem limitless. When players finish team practice, their individual practice might include mechanical skill drills in Sinatraa’s case—“I want to try to even get better at aiming”—or decision-making strategies, in Super’s role as main tank.

In contrast to the grandstanding and brawling that makes traditional sports headlines, Sinatraa says, “I think we all realize that it’s a team game. We make team mistakes, we make individual mistakes, but we could all be better than what we were in that day.”

Still, wins and losses take their toll. At the time of our conversation, the San Francisco Shock had lost to the Vancouver Titans in a 4-3 upset in the final round of tournament play. “We were definitely upset, all of us, and angry because we really thought that we could win and we expected to win, but we didn’t,” Super says.

Then there are the physical demands of esports. “Sitting all day is not necessarily the most healthy thing in the world … and players are doing incredibly repetitive movements from the shoulder down, all day, every day,” Lautenbach explains. “So making sure that their arms are in peak condition and [players] are being taken care of from a health perspective is super important to us.” (It’s one reason that NRG has partnered with 24 Hour Fitness.)

Finally, after hours

The team house plays a significant role in recovery. “You’re eating lunch, dinner with your teammates every day, always talking to them, having fun, laughing, making jokes, stuff like that,” Super explains. Sinatraa adds, “Architect and Rascal [teammates] will make me ramen a lot at night. We go swimming and hot tub together. We play pingpong.” The media room is also a place for bonding over Twitch streams or a movie.

It’s also an environment that supports the players’ growth as individuals. The house manager and team fill the gap where parents might normally provide advice, and Super says that fosters more independent thinking. Sinatraa adds that living with the team has made him “a nicer person” where previously he might have been more self-centered. That positive environment stems from the fact that, as Sinatraa says, “We’re all here for the same reason. No one wants to lose.”

Video & photo credit: Tom Casey, box24studio.com

Grooming: Chanel